Kodeclik Blog

How to implement hashmaps in Python

If you're coming from another programming language or learning about data structures, you've probably encountered the term "hashmap." But if you're working in Python, you might be wondering where to find this data structure. Let's clear up the confusion and explore how Python handles hashmaps.

What is a hashmap?

A hashmap (also called a hash table) is a data structure that stores key-value pairs and provides extremely fast lookups, insertions, and deletions. The "magic" behind hashmaps lies in their use of a hash function.

Here's how it works:

- Hashing: When you store a key-value pair, the hashmap passes the key through a hash function, which converts it into an integer (the hash code).

- Indexing: This hash code determines where in memory the value will be stored.

- Retrieval: When you look up a value by its key, the same hash function runs again, instantly pointing to the correct memory location.

This clever approach gives hashmaps their hallmark fast time complexity for lookups, insertions, and deletions—making them one of the most efficient data structures for associative arrays.

Why hashmaps matter

Hashmaps are incredibly useful for problems that require:

- Fast data retrieval by a unique identifier

- Counting occurrences of items

- Caching or memoization

- Implementing sets

- Building indexes or databases

Is there a separate hashmap Python data structure?

Here's the short answer: No, there is no separate hashmap class in Python.

Unlike languages like Java (which has HashMap, Hashtable, LinkedHashMap, etc.) or C++ (which has unordered_map), Python takes a simpler approach. The built-in dictionary (dict) is Python's hashmap implementation.

When Python developers talk about hashmaps, they're referring to dictionaries. The dict type uses a hash table implementation under the hood, giving you all the performance benefits of a traditional hashmap.

This is because Python focuses on simplicity and readability—why have multiple data structures when one well-designed option covers most use cases?

How do you implement hashmaps in Python?

Since Python's dict is the hashmap implementation, using hashmaps in Python is straightforward. Let's explore the basic ways to first create some dictionaries:

# Method 1: Using curly braces

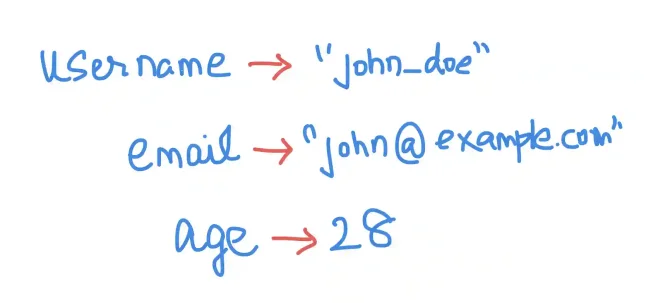

user = {

"username": "john_doe",

"email": "john@example.com",

"age": 28

}This method directly defines a dictionary with key–value pairs inside curly braces. Each key is mapped to its corresponding value, creating an easy-to-read literal dictionary.

# Method 2: Using the dict() constructor

user = dict(username="john_doe", email="john@example.com", age=28)Here, the dict() constructor is used to create the same structure. This approach is often preferred when keys are valid identifiers because you can skip using quotes around them.

Also, consider:

# Method 3: Creating an empty dictionary

empty_dict = {}

# or

empty_dict = dict()The above two lines show how to initialize an empty dictionary. You can then populate it dynamically by assigning keys later on.

Second, lets see how to add or update values:

# Adding a new key-value pair

user["location"] = "New York"

# Updating an existing value

user["age"] = 29

# Using setdefault (adds only if key doesn't exist)

user.setdefault("role", "user") # Adds "role": "user"

user.setdefault("age", 25) # Does nothing, "age" already existsThis code above demonstrates how to modify a dictionary. You can assign new key–value pairs, update existing ones, or use setdefault() to add a value only if the key doesn’t already exist.

You might also want to access values:

# Direct access (raises KeyError if key doesn't exist)

email = user["email"]

# Safe access using get() (returns None or default if key doesn't exist)

phone = user.get("phone") # Returns None

phone = user.get("phone", "N/A") # Returns "N/A"Here we see two common ways to retrieve data. Direct access retrieves the value but can raise an error if the key is missing. Using get() is safer since it allows specifying a default value.

You can also check for keys:

# Check if key exists

if "email" in user:

print(f"Email: {user['email']}")

# Check if key doesn't exist

if "phone" not in user:

print("No phone number on file")These examples show how to test whether a key exists in the dictionary using the in and not in operators — a fast way to control program flow when working with optional data.

You can remove items:

# Remove and return value (raises KeyError if key doesn't exist)

age = user.pop("age")

# Remove and return value with default

phone = user.pop("phone", None)

# Delete a key-value pair

del user["location"]

# Remove and return an arbitrary item (useful for draining a dict)

item = user.popitem()

# Clear all items

user.clear()The above code block illustrates various ways to delete entries. pop() removes a key and returns its value, while popitem() removes an arbitrary entry. del deletes specific pairs, and clear() empties the entire dictionary.

Finally, you can iterate through a dictionary:

user = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

# Iterate over keys

for key in user:

print(key)

# Iterate over keys explicitly

for key in user.keys():

print(key)

# Iterate over values

for value in user.values():

print(value)

# Iterate over key-value pairs (most common)

for key, value in user.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")Here we can see various ways to loop through a dictionary’s contents. You can iterate over just the keys, just the values, or both together using items(), which is the most typical pattern for reading or processing all entries.

Practical Example: Word Frequency Counter

Here's a real-world example of using a dictionary as a hashmap:

def count_words(text):

"""Count the frequency of each word in a text."""

word_count = {}

words = text.lower().split()

for word in words:

# Remove punctuation (simplified)

word = word.strip('.,!?;:')

# Increment count

if word in word_count:

word_count[word] += 1

else:

word_count[word] = 1

return word_count

text = "Python is great. Python is versatile. Python is popular."

result = count_words(text)

print(result)

# Output: {'python': 3, 'is': 3, 'great': 1, 'versatile': 1, 'popular': 1}This function counts how often each word appears in a given piece of text.

It starts by converting the entire text to lowercase and splitting it into individual words, ensuring that “Python” and “python” are treated the same. It then loops through each word, removing common punctuation marks like periods and commas so that “great.” becomes “great”.

Inside the loop, it uses a dictionary called word_count to keep track of frequencies: if a word has already been seen, its count is increased by 1; if not, it’s added to the dictionary with an initial count of 1.

Finally, the function returns the dictionary showing each unique word and how many times it occurs.

Key Requirements and Constraints

When using dictionaries as hashmaps, keep these rules in mind.

First, keys must be immutable: Strings, numbers, and tuples (containing only immutable items) work. Lists, sets, and other dictionaries cannot be keys.

# Valid keys

valid = {

"name": "Alice",

42: "answer",

(1, 2): "tuple key"

}

# Invalid - will raise TypeError

# invalid = {[1, 2]: "list key"}Second, keys must be unique: If you assign to the same key twice, the second value overwrites the first.

data = {"a": 1, "b": 2, "a": 3}

print(data) # Output: {'a': 3, 'b': 2}Finally, values can be anything: Any Python object can be a value, including other dictionaries, lists, or even functions.

What are hashmap-like alternatives in Python?

While the standard dict covers most use cases, Python's collections module provides specialized dictionary variants that add convenience for specific scenarios.

The defaultdict automatically creates default values for missing keys, making it perfect for counting items or grouping data without constantly checking if keys exist.

The Counter class is specifically designed for counting hashable objects and provides helpful methods like most_common() along with arithmetic operations for combining counts.

The OrderedDict was historically used to preserve insertion order, but since Python 3.7+ regular dicts maintain order too—though OrderedDict still offers unique features like order-sensitive equality checks and a move_to_end() method useful for implementing LRU caches.

For more advanced use cases, ChainMap groups multiple dictionaries into a single view, allowing you to search through layered configurations (like user settings overlaying defaults) without actually merging them.

All of these specialized types are still dictionaries under the hood—they simply add features that make certain patterns more readable and efficient.

Summary

Python's approach to hashmaps is elegantly simple: the built-in dictionary is your hashmap. There's no need for a separate data structure because dict provides everything you need with excellent performance and a clean, Pythonic API.

For specialized use cases, the collections module offers variants like defaultdict, OrderedDict, Counter, and ChainMap. These aren't replacements for dictionaries—they're enhanced versions designed to make specific patterns more convenient and readable.

Whether you're counting items, building a cache, or managing configuration layers, Python has a dictionary-based solution that fits your needs. Master these tools, and you'll have powerful data structures at your fingertips for virtually any problem you encounter.

Enjoy this blogpost? Want to learn Python with us? Sign up for 1:1 or small group classes.