Kodeclik Blog

How to compute a moving average in Python

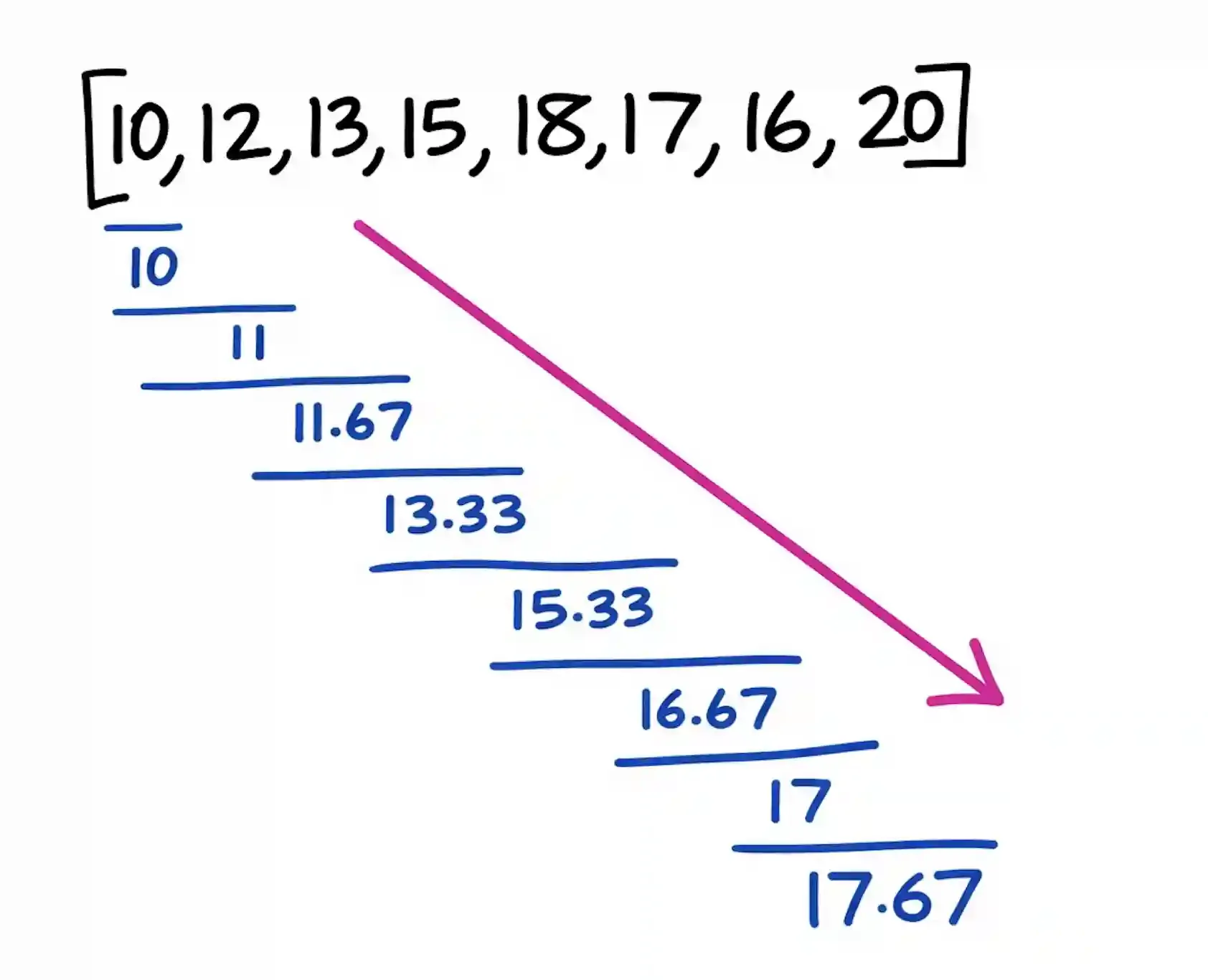

A moving average is one of the simplest (and most useful) ways to smooth noisy data. Instead of looking at each value in isolation, you average the most recent k values (the “window”). This reduces short-term fluctuations and makes trends easier to see—handy in everything from finance to sensors to monitoring system metrics.

Below are three ways to compute it in Python. In each method, we’ll compute a running moving average where the first few points use smaller windows (i.e., min_periods=1) and then switch to a full window once enough values exist.

We’ll use this sample data:

data = [10, 12, 13, 15, 18, 17, 16, 20]

window size w = 3Method 1: Pure Python loop (simple + clear)

This is the most beginner-friendly approach. We maintain a window of the last w points, update it as we go, and compute the average at each step.

from collections import deque

data = [10, 12, 13, 15, 18, 17, 16, 20]

w = 3

window = deque()

running_ma = []

for x in data:

window.append(x)

if len(window) > w:

window.popleft()

avg = sum(window) / len(window) # len(window) ramps up to w

running_ma.append(avg)

print("Running moving average:", [round(v, 2) for v in running_ma])

# Optional: show it step-by-step

print("\nStep-by-step:")

window = deque()

for i, x in enumerate(data):

window.append(x)

if len(window) > w:

window.popleft()

avg = sum(window) / len(window)

print(f"i={i}, x={x}, window={list(window)}, avg={avg:.2f}")This pure Python version computes the moving average by maintaining a small “window” of the most recent w values as it scans through the list from left to right. Each new value is appended to the window; if adding it makes the window larger than w, the oldest value is removed, keeping the window size bounded. At every step, the program averages the current contents of the window using sum(window) / len(window).

Because len(window) starts at 1 and grows up to w, this naturally creates a running moving average that “warms up” for the first few points (using 1, then 2, then 3 items, etc.) and then continues with a full fixed-size window once enough values have been seen.

This will give an output like:

Running moving average: [10.0, 11.0, 11.67, 13.33, 15.33, 16.67, 17.0, 17.67]

Step-by-step:

i=0, x=10, window=[10], avg=10.00

i=1, x=12, window=[10, 12], avg=11.00

i=2, x=13, window=[10, 12, 13], avg=11.67

i=3, x=15, window=[12, 13, 15], avg=13.33

i=4, x=18, window=[13, 15, 18], avg=15.33

i=5, x=17, window=[15, 18, 17], avg=16.67

i=6, x=16, window=[18, 17, 16], avg=17.00

i=7, x=20, window=[17, 16, 20], avg=17.67Method 2: Numpy (fast + vectorized)

If you’re working with large arrays, numpy is typically faster because it pushes the heavy computation into optimized C code.

This version reproduces the same “running” behavior (warm-up period, then full window).

import numpy as np

data = np.array([10, 12, 13, 15, 18, 17, 16, 20], dtype=float)

w = 3

# Prefix cumulative sum with 0 for easy window-sum differences

c = np.cumsum(np.insert(data, 0, 0.0))

# Warm-up: averages for the first (w-1) points using 1..(w-1) elements

warmup = c[1:w] / np.arange(1, w)

# Full windows: average of each length-w window

full = (c[w:] - c[:-w]) / w

running_ma = np.concatenate([warmup, full])

print("Running moving average:", np.round(running_ma, 2).tolist())The numpy approach speeds things up by avoiding Python-level loops for the main computation and instead using cumulative sums to get window sums in constant time per position. It first builds a cumulative sum array c where c[i] represents the sum of the first i elements (with a leading 0 inserted to align indices cleanly).

For full windows, the sum of any length-w window ending at position i is computed as a difference of cumulative sums: c[i] - c[i-w], and dividing by w yields the average. To match the “running” behavior, the code separately computes the warm-up averages for the first w-1 points using smaller denominators (1 through w-1) and then concatenates those with the full-window averages, producing the same running moving average as the loop method but typically much faster on large arrays.

The output will be:

Running moving average: [10.0, 11.0, 11.67, 13.33, 15.33, 16.67, 17.0, 17.67]Method 3: pandas rolling mean

If your data is time-indexed (dates, timestamps, log streams), pandas is extremely convenient. The rolling(...).mean() pattern is the standard.

import pandas as pd

data = [10, 12, 13, 15, 18, 17, 16, 20]

w = 3

s = pd.Series(data, dtype="float")

running_ma = s.rolling(window=w, min_periods=1).mean()

print(running_ma.round(2))The pandas method is the most concise because it delegates the moving-average logic to pandas’ time-series tools. The data is placed into a Series, and rolling(window=w, min_periods=1) creates a rolling window view over the series where each position corresponds to the last w values available up to that index.

Calling .mean() then computes the average for each window automatically. The key detail is min_periods=1, which tells pandas to compute an average even when fewer than w values exist early on—so the first point uses 1 value, the second uses 2 values, and so on until the window is full.

This makes the result a running moving average with warm-up behavior, and it integrates smoothly with pandas features like date indices, resampling, and plotting.

The run results will be:

0 10.00

1 11.00

2 11.67

3 13.33

4 15.33

5 16.67

6 17.00

7 17.67Applications

Moving averages are used in a variety of applications:

- Finance: smoothing stock prices/returns to see trend direction and reduce noise.

- Sensors & IoT: smoothing temperature, accelerometer, or power readings that fluctuate.

- Monitoring & operations: smoothing latency, error rate, CPU usage, throughput.

- Forecasting & modeling: creating stable features (e.g., “7-day moving average” of cases, sales, demand).

- Signal processing / anomaly detection: smoothing before detecting spikes, drifts, or outliers.

Summary

In this post, you learned what a moving average is and why it’s useful for smoothing noisy data so trends are easier to see. Each of the methods covered here produced the same output on the example data, but they differ in clarity, speed, and convenience depending on whether you’re learning, working with large arrays, or analyzing time-indexed data.

Enjoy this blogpost? Want to learn Python with us? Sign up for 1:1 or small group classes.